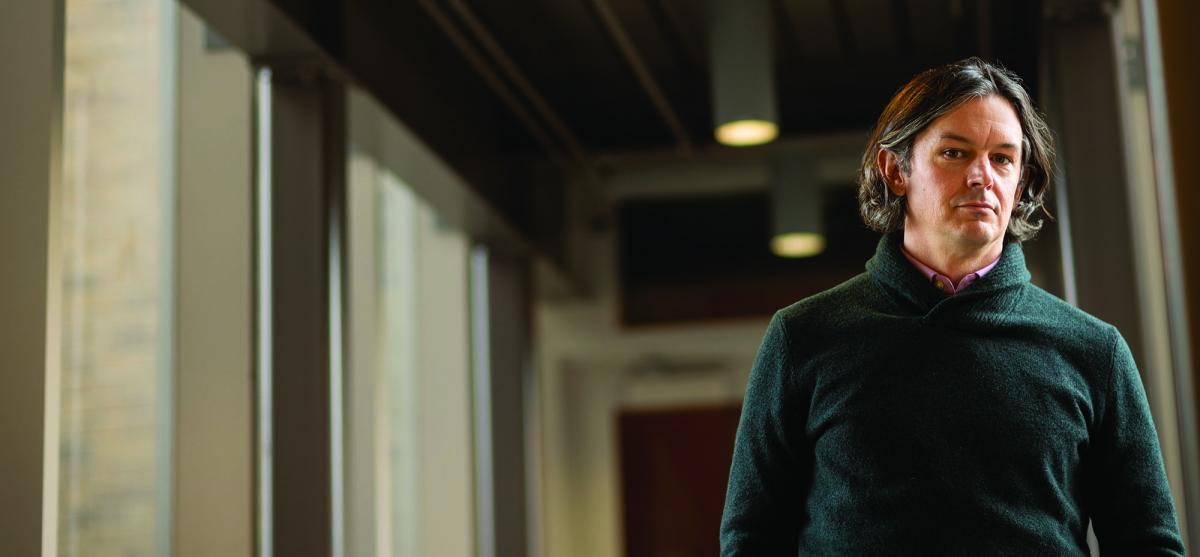

Did the trend toward majority votes over consensus in England’s 17th-century Parliament sow seeds of potential discord in future democracies?

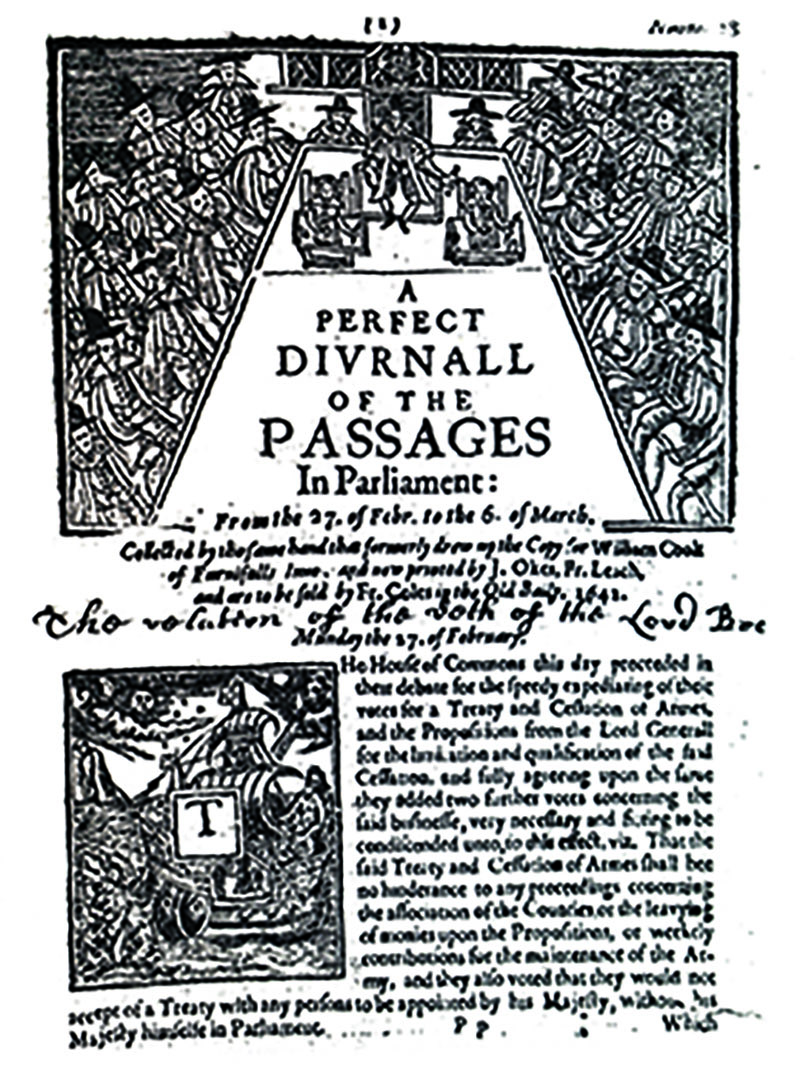

Prior to the 1640s, disagreements between members on policy or procedures were almost always resolved behind the scenes or through consensus. Even the name for an enumerated vote in parliamentary parlance—division—echoes the sense of disquiet a majority vote conveyed. In order to avoid enumerated votes, Parliament members would instead pigeonhole fractious proposals in committees or negotiate their way out of contentious issues.

“It’s very hard for societies or polities to admit being divided in an irresolvable way over questions that everyone cares about and things that are deeply significant. And that certainly was the case in the 1640s in England,” says Bulman.

There were many reasons for Parliament members to want to preserve at least the veneer of unanimity and paper over the fissures between factions.

During this period, a divided vote on an issue of import could be understood as a challenge to the legitimacy of Parliament, explains Bulman.

“One way to empathize with political actors of the 17th century is to remember that it was a status-obsessed society,” he says. “At the level of the aristocracy or even the gentry, an individual being involved in an open competition or struggle to get one’s way was considered dishonorable, as it portrayed an insecurity of your position or power.”

For that reason, even contested elections for office were rare.

“If you sought election to the House of Commons in opposition to another candidate, the thought was you maybe lacked moral rectitude or were acting selfishly,” Bulman says.

The importance of virtue—or the appearance of it, at least—was more than just a matter of personal character. It also operated as a mechanism to sustain social hierarchies.

“There’s clearly a structure of power behind the way that works. People with certain social characteristics, primarily landowning people or those involved in some form of public service, were able to separate themselves from those not born with certain social advantages,” Bulman says.

Lower-class people could not easily learn or display certain class-based attributes or their outward characteristics, keeping them from rising up the socioeconomic hierarchy.

Second, self-preservation must have been a factor. Parliament could be shut down peremptorily by the reigning monarch.

“There’s a point in the early 1640s where Parliament has so much leverage on Charles I that they probably can’t be dissolved, but prior to that, the king can dissolve Parliament at will,” says Bulman.

Perhaps most importantly, it was felt vital to present a united front on matters of foreign relations or war.

“Decision-making was at a premium when they were considering taxation, and they’re usually considering taxation because they’re considering warfare,” he says. “They clearly understood that if they were disunified in raising money to fight other European powers, it was a sign of weakness.”

The desire to project unanimity was so strong during the period, Parliament would, at times, engage in theatrical displays of unity after enumerated votes. For example, during the enumerated voting process, proponents supporting a measure would leave the chamber while their counterparts would remain, and the number of members in each group would be counted.

“After an enumerated vote, those who stayed in the chamber would actually leave and re-enter with the members who had left, in order to show unity,” Bulman explains. “After the vote, they had to ritualize the reunification of the polity. The distress of the enumerated vote had to be compensated for by a counter-ritual.”

Members on the losing side of an enumerated vote would then sometimes publicly confess to the chamber of having been mistaken in their view.

The acceptance of majority voting and majoritarian rule generally exported to the British colonies in North America.

“At the same time the colonies get majoritarian voting, they then go through the same transition from where elections are rarely contested to being commonly contested,” says Bulman.

Bulman’s next book, a global history of majority rule, and his ongoing research may contain lessons for those examining the challenges facing democracies generally.

“I think it’s important to examine the conditions under which majoritarian systems emerged to help us understand the nature of contemporary decision systems,” says Bulman.

As he digs deeper, Bulman finds his own views on majoritarian rule have shifted.

“It’s deepened my sense of the costs and benefits of our system and its proneness to various forms of corruption that consensual or more deliberative systems can avoid.”

While he is a historian, not a pundit, Bulman has been thinking about how innovative systems being tested at smaller scale might overcome some of the pitfalls of contemporary democracies.

“There are people experimenting with ways you could have more deliberation on policy questions outside of party or institutional constraints,” he says. “There are a lot of possibilities for consensus decision-making, which is appealing, but insistence on consensus can also be dangerous and has its own set of difficult questions.”